Teens are wired. Technology is so integrated with teenagers’ lives that creating useful and usable websites and apps for them is more critical than ever. To succeed in a world where the next best thing is a click away and text message interruptions are the rule, not the exception, website and app creators must clearly understand what teens want and how to keep them on a site.

To understand the expectations of a generation that grew up with technology and the internet, we conducted qualitative usability studies with teenage participants to identify guidelines for how websites can be improved to match this age group’s’ abilities and preferences.

Our research refutes many stereotypes, including the following:

- Mobile proficiency transfers across all devices

- Teens just want to be entertained online with graphics and multimedia

- Teens are tech-savvy

- Teens want everything to be social

Teens are not technowizards who surf the web with abandon. And they don’t like sites laden with glitzy, blinking graphics. Letting stereotypes steer your design can lead to disastrous outcomes.

Teenagers use the internet on many devices in various environments. For our research, we focused on web and app usability for laptops, tablets, and mobile devices. Although teens spend endless time texting and on social media, we didn’t focus on these activities because our goal was to derive design guidelines for mainstream websites and apps, not to help build the next Snapchat.

- The Research

- Teen Motivations for Using Websites

- Changes Over Time: Good and Bad News

- The Importance of Content and Layout

- Present Interesting Content Professionally and Clearly

- Speed Is Key

- Don’t Talk Down to Teens

- Let Teens Control the Social Aspects

- Design for Mobile Viewing

- Age-Group Differences

- Full report

The Research

We derived 130 usability guidelines for engaging teens and keeping them on your site. These recommendations are based on observational studies using multiple methodologies. A total of 100 users between the ages of 13 and 17 participated in three rounds of research: 38 teens in the original study for the first edition of this report, 46 teens in the second study, and 16 in the most recent study. We triangulated findings across three methods:

- Usability testing. We met with test participants one at a time and gave them tasks to perform, asking them to vocalize their thoughts as they attempted tasks. To keep the scenarios as authentic as possible, we matched the tasks with each teen’s actual interests and simulated real-world situations.

- Field studies. We observed teenagers in their homes and at school. During these site visits, we didn’t give users tasks to perform, but simply watched as they used the web the way they normally would in these settings.

- Interviews and focus groups. To gain further insight into their experiences and attitudes, we asked participants to offer stories and examples detailing how and when they used the web, and which sites they considered interesting and useful. We also solicited advice from teens on how to make websites appealing. Interviews were held before and after usability sessions, as well as during a focus group.

We conducted studies in the U.S., United Kingdom, and Australia, in cities and towns ranging from affluent suburbs to disadvantaged urban areas. We tested a roughly equivalent number of boys and girls on a total of 210 websites and 30 apps that covered a broad range of genres, including:

- School resources (University of Nottingham, Central Bucks High School West, BBC Bitesize, Quizlet)

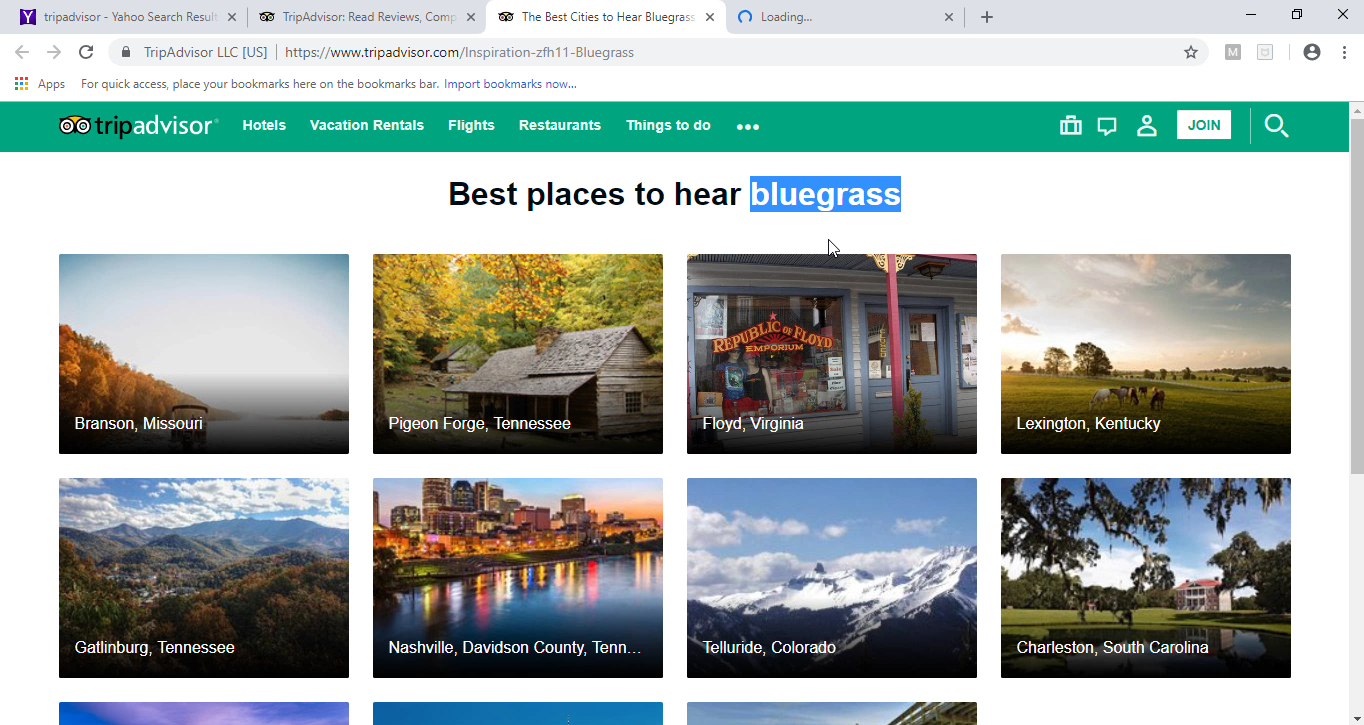

- Tourism/Arts & Entertainment (Visit London, TripAdvisor, ExploreChicago.com)

- Health (Australian Drug Foundation, TeensHealth, National Institute on Drug Abuse)

- Informational/Reference (Nature, Food Network, Scientific American)

- News (Buzzfeed, CNN, Weather.com, Daily Mail, The New York Times)

- Entertainment and Games (Stack AR, YouTube, Playlist.com, Geometry Wars)

- Ecommerce (Adidas, H&M, ASOS, Jabra)

- Corporate sites (McCormick, Unilever, Pepsi-Cola, Procter & Gamble, Samsung, Morton Salt)

- Government (Gov.UK, Australian Government main portal, Pennsylvania’s Department of Motor Vehicles, the U.S. White House, NASA)

- Nonprofits (Rotary International, Charity: Water, World Food Programme, National Wildlife Federation)

As these examples show, we tested both specialized sites that explicitly target teenagers and mainstream sites that include teens as part of a broad-target audience.

Teen Motivations for Using Websites

Teenagers access the web for myriad activities, including entertainment. Generally, they have a specific goal, even if that goal is just to keep themselves occupied for 10 minutes.

Although their specific tasks might differ from adults, teens are similar to adults in major ways: both groups expect websites to be easy to use and to let them accomplish their tasks. Like adults, teens are goal-oriented and don’t surf the web aimlessly; usability is thus as important for them as for any other user group.

Teens in our studies reported using the web or various apps for:

- School assignments

- Hobbies or other special interests (including learning new skills or finding fun activities)

- Entertainment (including music, videos, and games)

- News (including sports, current events, and entertainment)

- Learning about new topics

- Talking to friends

- Shopping

Even when teens don’t make purchases on ecommerce websites, they do visit them to research products and build wish lists for the credit-card–carrying adults in their lives.

Changes Over Time: Good and Bad News

The good news: Teens are becoming more successful at navigating websites and finding what they need. At the time of the third study, the oldest participant was born in 2001 and the youngest was born in 2005; therefore, all participants in this study grew up with access to computers. Between all three studies conducted over the last 15 years for this report, the amount of time teenagers spend on computers and mobile devices has steadily increased. How effective teenagers are with technology is correlated with the amount of time using technology.

Are teens getting better or are websites getting better? Probably a bit of both. We observed many of the same bad user habits among teens in our last study as we saw in our first study, back in 2004. Thus, the improved performance obviously stems in part from improvements in website design. That said, even though teens in our original study were heavy web users, teenagers today have even greater access to the internet and spend more time using it. This generation grew up with technology and is much more effective at using it than the participants in our first study (in which the oldest participant was born in 1988 and the youngest in 1992).

The bad news: Teens are not as invincible as some people think. Although teens might feel confident online, they do make mistakes and often give up quickly. Fast-moving teens are also less cautious than adults and make snap judgments; these lead to fewer successfully completed tasks.

Teens perform worse than adults for three reasons:

- Insufficient reading skills

- Less sophisticated research strategies

- Dramatically lower levels of patience

To improve your site’s usability among teens, you must consider all three factors. Also note that we have seen these factors in all our research with teenagers during a 15-year period, meaning that they are likely to continue to hold in the future, even if other teen habits may change as fads come and go.

Across different types of websites, teens had the most success on ecommerce websites, which often adhered to design standards and required little reading. Teens encountered the greatest challenges on large sites with dense content and poor navigation schemes. Government, nonprofit, and school sites were the biggest culprits of poor usability.

Despite usability improvements, we observed users struggling with the same issues as in previous years — as well as new issues created by emerging features and design approaches. Thus, both traditional and new guidelines must be considered as technology and people continually evolve; our new report contains 130 total guidelines, compared with 61 in the first edition and 111 in the second.

Many of the guidelines also apply to general audiences. For teens, however, these guidelines are even more important because the usability issues present bigger hurdles.

The Importance of Content and Layout

Write for impatient users. Nothing deters younger audiences more than a cluttered screen full of text. Teens can quickly become bored, distracted, and frustrated.

Teenagers don’t like to read a lot on the web. They get enough of that at school. Plus, their reading skills are not ideal — especially those of younger teens. Sites that were easy to scan or that illustrated concepts visually were strongly preferred to sites with dense text.

Applying proper web writing and formatting techniques is crucial in communicating with teens. Display content in small, meaningful chunks with plenty of white space. Small chunks help students retain information and pick up where they left off after the inevitable interruptions of text messages and phone calls.

Teenagers in our study were often overwhelmed with content on websites. To focus their attention on one area, we observed several teens highlighting text as they read down the page. These are some of their comments:

“Sometimes reading in black and white is hard. Highlight helps me read better.” – 16-year-old male

“I lost my train of thought, so I highlighted the text to focus more on it.” – 15-year-old female

Help teens learn and stay focused by choosing your words wisely. Use words that teens understand. Write in short sentences and paragraphs. Format key points or steps of a process using bullet points. Teens generally have poorer reading and comprehension skills than adults. If your site targets a broad audience, aim to write at a 6th-grade reading level (or lower). Writing at this level will help audiences of all ages — young and old — quickly understand your content.

One surprising finding in this study: teenagers dislike tiny font sizes as much as adults do. We’ve often warned websites about using small text because of the negative implications for senior citizens (and even people in their late 40s, whose eyesight has begun to decline). We’ve always assumed that tiny text predominated because most web designers are young and still have perfect vision, so we were surprised that small type often caused problems or provoked negative comments from our study’s teen users. Even though this audience is sufficiently sharp-eyed, most teens move too quickly and are too easily distracted to attend to small text.

“You go to Music and it’s real tiny. ... You look at this stuff and it’s hard to see. You have to squint. These are really small, and you can’t see. It needs to be a little bigger.” — 16-year-old female

Present Interesting Content Professionally and Clearly

Teens complained about sites they found boring. Dull content is the kiss of death if your goal is to keep teens on your site. However, not everything needs to be interactive and fancy. Although teens have a strong appreciation for aesthetics, they detest sites that appear cluttered and contain pointless multimedia.

Beware of overusing interactive features just because you design for younger audiences. Multimedia can engage or enrage teens, depending on its usefulness. The best online experiences for teens are those that teach them something new or keep them focused on a goal.

What’s good? The following interactive features all worked well because they let teens do things rather than simply sit and read:

- Online quizzes

- Forms for providing feedback or asking questions

- Online voting

- Games

- Features for sharing pictures or stories

- Features for creating and editing content

These interactive features let teenagers make their mark on the internet and express themselves in various ways — some small, some big.

The site type influences user expectations. For example, teens expect ecommerce and brand sites to look professional, and informational sites to look simple and polished. For the latter sites, presenting interesting content in a clear manner is much more attractive than experimenting with new sophisticated features. Teens can learn and feel engaged without the nonessential enhancements.

Speed Is Key

A slow-loading website is a deal-breaker. Whatever you do, make sure your site loads quickly. Slow, sluggish sites are frustrating to anybody, but they’re especially offensive to young audiences who expect instant gratification.

Think twice before you develop that super cool widget or include that 4K video. If it’s slow or buggy, forget it. Teens won’t have the patience for it. Because teens often work on older, second-hand devices — and sometimes have slow internet connections — fancy features and high-resolution multimedia might not work well.

“I hate this waiting. It’s very annoying ... I usually wouldn’t wait this long for a page to load. I would go to a different site, I would go to the next one.” — 17-year-old male

Don’t Talk Down to Teens

Avoid anything that sounds condescending or babyish. The proper tone can make or break your site. Teens relate to content created by peers, so supplement your content with real stories, images, and examples from other teens.

Some websites in our study tried to serve both children and teens in a single area, usually titled Kids. A grave mistake: the word “kid” is a teen repellent. Teenagers are fiercely proud of their newly won status, and they don’t want overly childish content — one more reason to ease up on the heavy animations and garish color schemes that work for younger audiences. We recommend having separate sections for young children and teens, labeled Kids and Teens, respectively.

Let Teens Control the Social Aspects

Facilitate sharing but don’t force it. Teens rely on technology for social communication, but they don’t want to be social all the time. They want to control what they share and how they share it. Sites that force teens to register and then automatically make their profile public violate trust. Parents and teachers teach teens to protect their privacy at a young age, and one of the things teens learn early is to avoid nosey sites.

When offering sharing options, include a link to copy the web address, as teens are likely browsing on their phones and want to share it directly with a friend. Participants in our studies often preferred using social media apps, like Snapchat, to message friends, so providing a Copy Link option allows them to send a direct message to a friend on any platform. When this functionality isn’t available, they tended to take screenshots and share them with friends. Though this behavior reaches their goal, from a business perspective, it hinders other teens’ ability to easily visit the content.

Design for Mobile Viewing

All of the teenagers in our most recent study had mobile devices, but not all had laptops or computers. Therefore, teens are often viewing your content from the palm of their hand.

Complex mouse gestures often don’t translate well to mobile. The adoption of portable devices requires that you design a website so that it doesn’t compromise usability.

Teens often work on touch-enabled devices, making interactions that require precision — such as dropdown menus, drag-and-drop, and small buttons — difficult. Design elements such as rollover effects and small click zones are also problematic, if they’re usable at all. Small text sizes and dense text make reading difficult.

Media portrays teens as competent computer jockeys. In reality, teens’ overconfidence combined with their developing cognitive abilities means they often give up quickly and blame the website’s design. They don’t blame themselves, they blame you.

Age-Group Differences

The following table summarizes the main similarities and differences in web-design approaches for young children, teenagers, college students, and adults. (The findings about children are from our studies with 3–12-year-old users; the findings about college students are from our study with 18–25-year-old users.)

|

|

Children |

Teens |

College Students |

Adults |

|

Search |

Bigger reliance on bookmarks than search, but older kids do search |

Heavy reliance on search; some difficulty formulating search queries; click topmost results in SERP |

Heavy reliance on search; some difficulty formulating search queries; click topmost results in SERP |

Heavy reliance on search; some difficulty formulating search queries; click topmost results in SERP |

|

Scrolling |

Don’t scroll (younger); some scrolling (older) |

OK scrolling |

OK scrolling |

OK scrolling |

|

Animation and sound effects |

Attend to things that move and make sounds |

Might appreciate them to some extent, but overuse can be problematic. |

Dislike them; autoplay sound disruptive in dorms |

Dislike them; autoplay sound disruptive at work |

|

Patience |

Want instant gratification |

Hate waiting for things to load or having to close pop ups; easily distracted |

Want answers quickly; no patience for complicated interactions; easily distracted. |

Want answers quickly, but more likely to wait than college students |

|

Trust & credibility |

Want good initial reaction; Credibility less important because goal is mainly entertainment |

Difficulty judging credibility |

Very critical; quick to judge websites |

Less critical of websites than college students; still quick to judge |

|

Tabbed browsing |

Not used |

Used often; few tabs |

Used often; many tabs open at a time |

Commonly used; varies depending on technical comfort |

|

Disclosing private info |

Hesitant to enter information |

Hesitant to enter information |

Less ‘fear’ of technology and therefore (often recklessly) willing to give out personal info |

Often recklessly willing to give out personal info on sites they trust |

|

Advertising |

Difficulty distinguishing from real content |

Like discounts but hate popups |

Have a keen eye for ads and don’t like being tricked |

Mostly avoid ads but appreciate them when they are relevant and unobtrusive |

|

Age-targeted design & content |

Crucial, with very fine-grained distinctions between age groups |

Want age-appropriate content; prefer sites with neutral graphics rather than childish ones |

Want age-appropriate information, but don’t want everyone to sound ‘hip’ |

Less critical for most sites |

Clearly, there are many differences between age groups. The highest usability level for teens comes from designs that are targeted specifically at their needs and behaviors, which differ from those of adults and young children. As the table shows, this is true both for interaction design and for more obvious factors, such as topics and content style.

Full report

The new edition of the report on our user research with teenagers, with actionable UX design guidelines is now available for download.